Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s original stories.

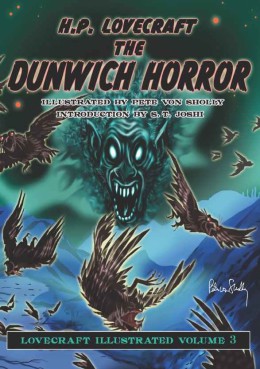

Today we’re looking at the first half of “The Dunwich Horror,” first published in the April 1929 issue of Weird Tales. You can read it here; we’re stopping this week at the end of Part VI.

Spoilers ahead.

“Then too, the natives are mortally afraid of the numerous whippoorwills which grow vocal on warm nights. It is vowed that the birds are psychopomps lying in wait for the souls of the dying, and that they time their eerie cries in unison with the sufferer’s struggling breath. If they can catch the fleeing soul when it leaves the body, they instantly flutter away chittering in daemoniac laughter; but if they fail, they subside gradually into a disappointed silence.”

Summary: Dunwich, Massachusetts, lies in an isolated region characterized by the snaky windings of the upper Miskatonic River, and round-headed hills crowned with stone circles. Its overgrown forests and barren fields repel rather than attract visitors. The few homesteads are dilapidated, their owners gnarled and furtive. Nightfall brings an eerie chorus of bullfrogs and whippoorwills, to which fireflies dance in abnormal profusion. The village itself is repellently ancient, and the broken-steepled church now serves as the general store. The inbred natives are prone to deeds of violence and perversity, and young people sent to college seldom return.

Tales of witchcraft, Satanism and strange presences dog Dunwich. Human bones have been unearthed from the hilltop circles; a minister disappeared after preaching against the hill noises “which needs have come from those Caves that only black Magick can discover, and only the Divell unlock.” The whippoorwills are believed to be psychopomps. Then there’s old Wizard Whateley.

Locals fear the remote Whateley farmhouse. Mrs. Whateley died a violent and unexplained death, leaving behind a deformed albino daughter, Lavinia. Lavinia’s only learning came from her half-mad father and his worm-riddled books. The two celebrate a witch’s calendar of holidays, and one Candlemas night she gives birth to a son of unknown paternity. Whateley boasts that one day folk will hear Lavinia’s child calling his father’s name from atop Sentinel Hill.

Little goatish Wilbur brings changes to the family homestead. Old Whateley begins a program of cattle purchases, though his herd never seems to increase or prosper. He repairs the upper stories of his house, gradually opening the whole space between the second story floor and the roof. The upper windows he boards. The doors opening to the upper floor he locks. The family lives entirely on the first floor, but visitors still hear odd sounds overhead.

Wilbur becomes his grandfather’s avid student. Preternaturally precocious, at age ten he looks like a grown man and has acquired an astonishing occult erudition. Old Whateley dies on Lammas Night, 1924, after admonishing Wilbur to give “it” more space. He must also find a certain long chant that will open the gates to Yog-Sothoth, for only “them from beyont” can make “it” multiply and serve them. Them, the old ones that want to come back.

Poor Lavinia disappears. Wilbur finishes making the farmhouse a cavernous shell and moves with his library into sheds. Dogs have always hated him; now people hate and dread him, too, suspecting he’s responsible for certain youthful disappearances. The old-time gold, that supports his continued cattle-buying, silences inquiry.

Dr. Henry Armitage, librarian at Miskatonic University, once visited the prodigy Wilbur in Dunwich. Late in 1927, he receives the huge, shabby “gargoyle” at the library. Wilbur has brought along a partial copy of John Dee’s Necronomicon translation, to compare with the Latin version under lock and key at Miskatonic. He’s looking for a specific incantation containing the name Yog-Sothoth. While he works, Armitage reads a passage over his shoulder. It concerns the Old Ones who walk serene and primal between the spaces man knows. By their smell men may know them, but even their cousin Cthulhu can spy them only dimly. Yog-Sothoth is the key to the gate where the spheres meet. Man may rule now, but the Old Ones have ruled here before, and will rule here again.

No great skeptic, it appears, Armitage shivers. He’s heard of the brooding presences in Dunwich, and Wilbur strikes him as the spawn of another planet or dimension, only partly human. When Wilbur asks to borrow the MU Necronomicon, to try it out in conditions he can’t get at MU, Armitage refuses. More, he contacts the other keepers of the dread tome and cautions them against Wilbur. Then he starts an investigation into Dunwich and the Whateleys that leaves him in a state of spiritual apprehension.

In August 1928 comes the climax Armitage has half-expected. A burglar breaks into the library, only to be felled by a huge watchdog. Armitage gets to the scene first, with his colleagues Professor Rice and Dr. Morgan. They bar curious onlookers, for what the three find is sanity-shaking.

Wilbur Whateley lies on the floor, dying. The watchdog has torn off his clothing to reveal what he’s always hidden, a torso ridged like crocodile hide and squamous like snakeskin. But that’s far from the worst. Below the waist, all humanity vanishes into black fur, sucking tentacles, saurian hindquarters, rudimentary eyes in each hip socket, and a trunk or tail like an undeveloped throat. Instead of blood, green-yellow ichor oozes from his wounds.

Wilbur gasps in an inhuman language Armitage recognizes from the Necronomicon. The name Yog-Sothoth punctuates the muttering. Then Wilbur gives up a ghost from which whippoorwills flee in shrieking terror.

Before the medical examiner can arrive, his corpse collapses into a boneless white mass. Too obviously, Wilbur took “somewhat after his unknown father.”

What’s Cyclopean: Nothing’s cyclopean, but there’s a bridge with a tenebrous tunnel. Then there are the armigerous families—bonus points to anyone who didn’t have to look that one up.

The Degenerate Dutch: How do you feel about the rural poor? Did you remember that they are scary and degenerate? “The average of their intelligence is woefully low, whilst their annals reek of overt viciousness.” I know you’re one, but what am I?

Mythos Making: Yog Sothoth is the gate and the key. If someone asks if you’re the gatekeeper, say no. This story also adds Dunwich to the Lovecraft County Atlas, details the weird cousins that Cthulhu hates dealing with every holiday dinner, and tells you all you’re going to get about Miskatonic’s architecture and security system.

Libronomicon: The Whateleys have a surviving copy of Dee’s translation of the Necronomicon, but it’s missing a few pages. Wilbur is forced to check alternate editions to find what he needs. Is anyone else worried by the similarities between the Necronomicon and The Joy of Cooking?

Madness Takes Its Toll: Lavinia’s dad suffers from both madness and wizardry, never a happy combination.

Anne’s Commentary

“The Call of Cthulhu” was the first of the core Mythos tales. “The Dunwich Horror” was either the second or the third, depending on whether you admit Charles Dexter Ward to the select club. Either way, by 1928 Lovecraft had written several stories I consider early masterpieces, more or less tentative: “Call” and Ward along with The Dream Quest of Unknown Kadath, “The Strange High House in the Mist,” “The Color Out of Space,” “Pickman’s Model,” and “The Rats in the Walls.”

This reread strengthened my impression that “Dunwich Horror” outdoes all its worthy predecessors, yes, even the iconic “Call.” One may trace its origins to Lovecraft’s travels in the “decadent Massachusetts countryside” around Springfield, or maybe Athol, or maybe the Greenwich that would drown in the Quabbin Reservoir in 1938, One may note the use Lovecraft makes of New England legends, like blasted heaths and Native American burial grounds, cryptic hill noises and whippoorwill psychopomps. But in the end, Dunwich and its horrors are all his own, and it won’t be until 1931 that he rivals this feat of small-scale/cosmic-scale world-building with his shadowed Innsmouth.

Formally, “Dunwich Horror” is as sound as the roots of Sentinel Hill. Lovecraft fills the novelette-length story with a novel’s worth of material, but gracefully, efficiently. Section I gives us an atmospheric travelogue, and the narrator doesn’t simply observe the setting from the tranquil perch of omniscience. He looks through the eyes of a lost motorist, one who knows nothing about the place but who nevertheless shudders at its odd couplings: vegetable luxuriance and architectural dilapidation, symmetry and squalor, uncannily vocal fauna and furtively silent locals. The motorist having escaped, narrator gives us a compact weird history of Dunwich. Witches danced there in Puritan days, and before them the Indians called forbidden shadows from the rounded hills. The very earth rattled and groaned, screeched and hissed with the voices of demons, as a certain minister pointed out, before his disappearance.

On to section II, where we meet the Whateleys, including the dubiously-conceived Wilbur. There’s a lovely scene-let, in which a townsman sees Lavinia and Wilbur running up Sentinel Hill one Hallowe’en, darting noiseless and naked, or is the boy wearing shaggy pants and a fringed belt?

Section III details Wilbur’s preternaturally swift maturation and the increasingly odd doings at the Whateley farm. Section IV sees old Whateley off, with a doctor present to overhear his mutters to Wilbur about Yog-Sothoth and opening gates. It also gives us the first instance of whippoorwills waking a soul’s departure. Lovecraft makes great use of the psychopomp legend in characterizing each victim and in escalating tension. The whippoorwills fail to catch old Whateley’s soul, because he’s too canny for them. They catch Lavinia’s weaker soul with gleeful nightlong cachinnations. But Wilbur’s soul? Whoa, that’s so damn scary the whippoorwills flee from it.

Section V brings odd scholar Wilbur to Arkham and introduces Lovecraft’s most efficacious hero, Henry Armitage, librarian. It also gives us a gorgeous passage from the Necronomicon, a virtual encapsulation of the Mythos and why it matters to us, the doomed. If this is a fair sample of Alhazred’s writing, he was a poet of some skill, however mad. “After summer is winter, and after winter summer.” Nice, and the kicker is that “winter” is man’s reign, while “summer” is the reign of the Old Ones. All a matter of perspective, baby.

Also cool is that for once we have an educated character who isn’t entirely incredulous of the Mythos, and why should Armitage be, who’s had access to the most potent of its tomes?

Section VI gives us the first climax, Wilbur’s attempt on the Necronomicon and his death to an old nemesis, the infallible canine. Armitage’s allies make a first appearance and see that which will bind them to the developing cause. And just how weird was Wilbur, all these years? Lovecraft eases off on the unnamable thing, even noting that “it would be trite and not wholly accurate to say that no human pen could describe [Wilbur.]” Instead Lovecraft’s pen details his physiological abnormalities with the scientific minuteness characteristic of the central Mythos tales. No vagueness here, instead hip-eyes in pinkish, ciliated orbits! Ridgy-veined pads that are neither hooves nor claws! Purple annular markings with spaces between the rings that pulse from yellow to sickly grayish white due to some obscure circulatory phenomenon!

Many weird tales have ended with something less spectacular than Wilbur’s exposure and the closing observation that he “had taken somewhat after his unknown father.” But Lovecraft’s on a roll, and he’s only halfway through the Dunwich horrors at this point. Nor will they fail to get more and more horrible, until we get what Lamb imagined possible, a “peep into the shadowland of pre-existence.”

Note: I’ve always wondered why some ethnologists think the remains within the hilltop circles are Caucasian rather than Native American, as you’d expect in a burial ground of pre-European vintage. Maybe Vikings made it to Dunwich before the English? Or maybe the bones aren’t all that old and represent the European victims of wizards like the Whateleys? Or maybe the ethnologists are just wrong about their origin? Or what? Speculation welcome!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Lovecraft’s list of stories is long, and there are a few hidden gems—“Out of the Aeons” leaps to mind. But overall, I’m discovering on reread that the much-reprinted favorites are at the top of everyone’s list for a reason. This one’s a terrific, atmospheric piece, with just enough of old Howard’s signature flaws to mark it clearly as his work.

Atmospheric, mind you, because the plot isn’t really what anyone’s here for. If you lay with horrors from beyond earth’s three dimensions, you’re likely to give birth to horrors from beyond earth’s three dimensions, and then you’re likely to get eaten by horrors from beyond earth’s three dimensions—yes, we know, we’ve all heard this warning a hundred times. (We have, right? It’s not just my family?) But everything, from the winding Miskatonic to Wilbur’s body odor, is described in loving or loathing detail. There’s an extended excerpt from the Necronomicon, and as much as you could hope to know about Yog Sothoth and Miskatonic University, and the heroic brotherhood of Necronomicon-guarding librarians.

And the whippoorwills. They have no bloody place in the thoroughly scientific, fearfully materialistic Mythos, but they pull the whole story together and give it an extra layer of shivering creep that you couldn’t get from a dozen black gulfs. Old Whateley sets the tone, telling the reader as well as his family how to read their response to each death. And then, just as you get into the rhythm of listening to hear whether they’ve caught each latest soul for their own, “against the moon vast clouds of feathery watchers rose and raced from sight, frantic at that which they had sought for prey.” Brr.

Poor Dunwich—too far from Arkham to get much casual traffic, and dismissed from the start as relegated to back-country “degenerates.” It’s not destroyed as Innsmouth was, or Greenwich, but relegated just as thoroughly to the memory hole. All anyone does to Dunwich is pull down the road signs. But a Massachusetts town with no industry, and no visiting tourists for the fall colors… even without government raids or eminent domain claims, it may not last long.

And poor Lavinia. She suffers from the start, with Lovecraft not stopping at the Evil Albino trope, but going on to remind us continually that she’s ugly and her father is a crazy wizard. She has bad taste in men inhuman entities from beyond space-time. And then she gets eaten by her own kid. It’s no fun to be a woman in a Lovecraft story, and worse if you have male relatives.

We leave off this week with Wilbur’s death, or at least discorporation. It’s a great scene, one that invokes unnamability before shrugging and going ahead with the naming—while letting us know that whatever we’re picturing, it doesn’t do Wilbur’s corpse justice. And best not to even think about the father whose influence gave the boy sucker tentacles and extra eye-spots and a tail with an undeveloped mouth. That tail! Is it undeveloped because Wilbur’s only half Old One? Or because even Old Ones have appendix equivalents from their own version of evolution?

Say what you will about Lovecraft, he could cook up an inhuman body plan like nobody’s business.

(P.S. See here for a real-world example of researchers being dense and stubborn about the ethnic origin of bones. It sounds like a Lovecraftian WTF, but turns out to be something we still haven’t outgrown.)

Next week, we pick up with Part VII of “The Dunwich Horror,” and the terrible events that follow Wilbur’s demise.

Ruthanna Emrys’s non-Hugo-nominated neo-Lovecraftian novelette “The Litany of Earth” is available on Tor.com, along with the more recent but distinctly non-Lovecraftian “Seven Commentaries on an Imperfect Land and “The Deepest Rift.” Her work has also appeared at Strange Horizons and Analog. She can frequently be found online on Twitter and Livejournal. She lives in a large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story. “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com, and her first novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen. The second in the Redemption’s Heir series, Fathomless, will be published in October 2015. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.